Crowns

SERBIA — THE HOMELAND OF ROMAN EMPERORS: AURELIAN (270-275)

Triumphs of a Pannonian warrior

He was the border commander and the cavalry commander of Claudius II Gothicus who made him his heir on his deathbed. Valerian spoke of Aurelian as the Savior of Illyricum and the Renovator of Gallia. He terminated with success the war against the Goths, punished Germanic tribes that invaded Italy, made the city of Rome secure by building walls around it, regained Gallia, Spain and Britain from the hands of usurpers, stabilized the frontier on the Danube, defeated the Palmyrene Kingdom reigned by Queen Zenobia, skillful and seductive like Cleopatra. On the east road of Alexander the Great he was killed by those who he trusted the most

By: Aleksandar Jovanović Ph. D.

In the course of the fatal Kiprian's plague of the third decade of the 3rd century AD, when people weren't particularly pleased about the birth of new life, in a small village property (villa rustica) near Sirmium was born a boy named Lucius Domitius Aurelianus, a future emperor of the Empire. His father was a peasant, honorable representative of a small piece of land within a large property of Aurelius, a rich landlord who had a senatorial rank. Probably, in order to invoke a better fate and plentiful fortune, he named his son after the man whose comfortable life and probably a certain kindness that was visible to him on a daily basis. Aurelian's mother was a lower rank priestess of Sol's cult and served in the nearby chapel dedicated to this deity. In the course of the fatal Kiprian's plague of the third decade of the 3rd century AD, when people weren't particularly pleased about the birth of new life, in a small village property (villa rustica) near Sirmium was born a boy named Lucius Domitius Aurelianus, a future emperor of the Empire. His father was a peasant, honorable representative of a small piece of land within a large property of Aurelius, a rich landlord who had a senatorial rank. Probably, in order to invoke a better fate and plentiful fortune, he named his son after the man whose comfortable life and probably a certain kindness that was visible to him on a daily basis. Aurelian's mother was a lower rank priestess of Sol's cult and served in the nearby chapel dedicated to this deity.

These parents left a deep and long-lasting mark upon the life of the future emperor. The father's simplicity, temperance and thriftiness, permeated with a fear of poverty, taught him to nurture a genuine virtue and insightful sense of justice measured in land and invested efforts. From his mother, he inherited devotion to the cult of Sol and acknowledgment that through success, through the levels of purification and spiritual transformation, one could reach desirable heights. His father, who recognized the boy’s fighting spirit and military destiny, didn't force him to stay upon the property, although capable workers were in short supply.

Admitted to army as an ordinary soldier, Aurelian pursued a successful career upon his virtues, incomparable courage and intelligence: he was a centurion, tribune, legion prefect, commander of a frontier and, in the Gothic War during the reign of Claudius II, he was a cavalry commander as well. He was a consul together with Valerian, who served as emperor in the period from 253 to 260 AD and who spoke of Aurelian with enchantment, using festive vocabulary, dubbing him the Savior of Illyricum, Renovator of Gallia, and comparing him with great Scipio. A Senator of the high rank and reputation, Ulpius Crinitus, in whose veins flowed the blood of Trajan, adopted this temperate man from Pannonia, gave him his daughter Severina in marriage and shared his great glory and honorable origins with Aurelian's respectability.

Emperor Claudius, who also originated from our region, Moesia in fact, had designated him as his successor on the throne, a decision accepted by the Senate and, with great gratification, by the troops.

IRON MERCY The core of Aurelian's interests was, even after his appointment to emperor, the army that he wanted to train to be resolutely effective, but moreover praiseworthy and merciful. In his decisions, which were concise and laconically short, he regulated a number of relations within the army, his personal example could be recognized in them. From his soldiers he expected moderation, thriftiness and hard work; their weapons to be checked and at hand, their clothing and horses ready for instantaneous embark, the soldiers to live in their homes simply, without vices and cleverly, not to devastate fields of wheat or to steal sheep, poultry or grapes, without extortion of landlords for salt, oil or woods. Gambling, drinking, debauchery and sorcery were forbidden. Salary was sufficient for a soldier and goods should be acquired by plundering the enemies and not by causing tears inside the Roman Provinces.

Indeed, in Aurelian's vision of army his personal example could be recognized. Aurelian's five-year long reign was full of wars, military successes and endeavors that are to be remembered. The Emperor bore, justifiably and honorably, bellatoris- the ephitet of a hero. This epithet is related to Mars but also adjoined to Pannoniam Silvanus, god from Aurelian's homeland.

He terminated with success the war against the Goths, punished Germanic tribes that invaded Italy, made the city of Rome secure by building walls around it, regained Gallia, Spain and Britain from the hands of usurpers, stabilized the frontier on the Danube, defeated the Palmyrene Kingdom reigned by Queen Zenobia, skillful and seductive like Cleopatra, and with indisputable right obtained the appropriate title of Resturator orbis.

His merits in this field prevail and Emperor Diocletian's statement about Aurelian seems quite truthful: ”...he would manage better and prove himself more as an army commander than ruler of the Empire.”

FATEFUL KINDNESS At the end of 274 AD he began the eastern warfare against Persia, the measurement of Alexander's vestiges. During the march, which was quite promising, between Byzantium and Perinthus, he fell victim to a conspiracy organized by the men he loved, elevated and had complete confidence in. Pannonian openness took deprived him of the ability to recognize a turncoat, the vanity and treachery that stood beside him.

His death was deeply and sincerely mourned by the troops, condemned in the Senate; he gained common recognition as a valiant and successful emperor, capable and severe reformer in a country on the decline. He was buried near the place where he died in the Coenofrurium fort where a temple above the grave was built as well as a column dedicated to deified Aurelian. We believe that a kenotaph, a sacral memento, was built to this emperor in his fatherland as well.

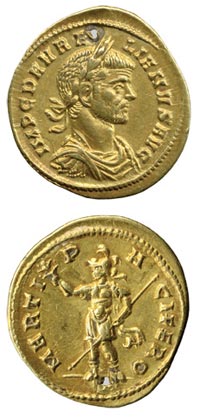

The statues of Aurelian from our regions are not known. On coins he is represented as an invincible emperor. A bust, following the rule, doesn't match with the axis of the obverse; it is slightly put forward and represents a movement forward, an attacking position on the enemy. Usually armor and officers’ cloak were seen on him, which emphasizes the military principle in the representation. His neck is strong and wide, never bent, and indicates that he is never choosing retreat before an enemy. Hair and beard are depicted in militaristic short style and done in an impressionist manner; differentiation of the character is barely visible. Severe expression emphasized by a sharp look and pressed lips, is dominating. A wrinkled forefront is in contrast to the flat, almost youthful, surfaces of face. The representation possesses an accentuated victorious attitude expressed in the bravery of a mature man of unspoiled beauty and honor.

It is interesting that in Aurelian's representations on the obverse of coins were emphasized his armor and shield, equipment for protection, which the emperor himself called arma, while to signify the arms for attack was used the term ferramenta samiata. This is the expression of the inherent caution of a man who looked after his soldiers and territory and to whom defense was more important than conquests, which is testified by Aurelian's wall in Rome (Todd 1978) and remains of the parts of military frontiers across the Empire.

A PORTRAIT FROM SERBIA  With the representation of the emperor as a stormy, strong and invincible man, is illustrated a picture of a battlefield where Aurelian proved himself in countless direct fights against the enemy. A proven example is that in only one battle with the Sarmatians he defeated 48 combatants and in the forthcoming battles the number of killed enemies reached 950. These types of Aurelian’s feats were praised by soldiers and glorified in their fierce song with a refrain that indicates a thousand killed rivals: millе, mille, mille occidit. With the representation of the emperor as a stormy, strong and invincible man, is illustrated a picture of a battlefield where Aurelian proved himself in countless direct fights against the enemy. A proven example is that in only one battle with the Sarmatians he defeated 48 combatants and in the forthcoming battles the number of killed enemies reached 950. These types of Aurelian’s feats were praised by soldiers and glorified in their fierce song with a refrain that indicates a thousand killed rivals: millе, mille, mille occidit.

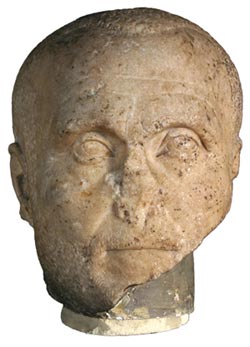

Perhaps in only one damaged marble head from an, unfortunately, unknown archaeological site in Serbia, exists the indications of Aurelian’s portrait. The studio that produced it was local, thus the portrait displays certain inconsistency and carelessness, but the fundamental impression is remarkable and possesses quality of magnificence.

Furthermore, there is little to be said about the building activity by this emperor on our territory. Generally, one could assume that after the loss of Dacia during Aurelian’s reign the frontiers on the Danube were established, which was testified in several fortresses. He saw Sirmium as his homeland and returned very often. It is probable that Sirmium could be linked with the coinage from an unknown mint, with a coin fragment bearing on the reverse an illustration of a dolphin. The dolphin motif could symbolize a flotilla that existed in Sirmium, but through the homophony and co-radical relationship of words δελφίς, ινος (dolphin) and δελφύς, ύος (womb, train of a skirt), homeland, that is to say the place of Aurelian’s birth.

Aiming to achieve the absolute unity of the Empire, he established the imperial cult of Sol, god of emphasized soteriological prominence, which was easily acceptable among the people of the unstable 3rd century A.D., when devastations of all sorts threatened the shield of the pantheon of Capitol and compelled the esoteric syncretistic beliefs of a deceitful hope coming from the other side. In those circumstances, the cult of Sol, which was based upon a long tradition, moral virtue, and direct correlation with the cult of Mithra and the indisputable victory over darkness and which could be experienced with every new morning, gained significant reverence. Aurelian had a temple dedicated to Sol built at the base of the Quirinal in Rome, donated the statues representing Sol and Baal, cult spoils brought from Palmyra and presented 15,000 pounds of gold to the temple; he also introduced games - agon Solis - in honor of this deity. He considered himself the god's (Sol's) investiture on earth. This scheme is especially present on the coinage from Serdica, metropolis of the new province of Dacia Mediteranea that was founded by Aurelian.

TRIUMPHAL CHURCHES  Among the more important temples in the Balkan provinces of the Empire should be mentioned a temenos (Greek word for sacred space) in Thessalonica with monumental cult statue of Sol in front of the main entrance of the city. Among the more important temples in the Balkan provinces of the Empire should be mentioned a temenos (Greek word for sacred space) in Thessalonica with monumental cult statue of Sol in front of the main entrance of the city.

Facts about this sort of building activity by Aurelian in his homeland, that is to say in the region of Sirmium, are missing. Indirectly, only an unclear and chronologically uncertain trace can be followed. This includes a well-known text about the martyred death of five Christians-stonecutters in the surroundings of Sirmium during Diocletians’ persecutions - Passio sanctorum IV coronatorum. Diocletian requested that stonecutters from Sirmium make a monumental 25 foot tall statue of Sol. When the statue, with the help of Christ, was sculpted in stone from Tassos, the Emperor brought a decision to build a temple of Sol on Mons pinguis (Debelo brdo) and place the statue there.

But, it would be hard to expect that a monumental statue, which was even gilded, would have been commissioned if a temple didn’t exist. It seems that an older temple of Sol certainly existed, probably built in the time of Aurelian, to which Diocletian wanted to make donations, as he deeply respected his precursor. This possibility is indicated by the remaining sculptural inventory that Diocletian commissioned from the skilful stonecutters. These include deer - in a quadriga (chariot) (?) - that are known from Aurelian’s triumphal iconography. Namely, in the great imperial triumph celebrated in Rome in 274 AD, the victories achieved in the south were represented by quadriga guided by elephants and victories in the north were depicted by a quadriga guided by deer. This is the expression of Apollo’s, actually Achilles’ triumph over hyperborean, northern meridians.

One can recognize the reflections of Aurelian’s triumph over the enemy in army belt sheaths made of bronze plate. On one group of these objects was represented a horseman with a spear in his raised right hand, behind him is a silhouette of a soldier and below is a dog or, more often, a lion. The representation is similar to illustrations of Thracian horseman or, rather, to Alexander’s royal hunt and representations of Apollo to whom a Thracian horseman was often identified. It can be postulated that on these images was represented the identification of the emperor (Aurelian?) with Apollo - Sol or with Bellerofon.

On the second group of these sheaths was represented a horseman in an attacking position with an enemy who was fallen under a horse. This representation was based upon the well-known Lisipus example that shows Alexander the Great in battle. It seems that representation of this kind should also be linked to Aurelian and his triumph in the East. This possibility is indicated by the existence of an identical representation on Aurelian’s armor from coins minted in Serdica .

THE SECRET OF DANUBIAN HORSEMEN But the most interesting ensemble of this kind are the icons illustrating horsemen from Danubian region. This cryptic cult of unreachable meaning and sacral explanation was testified by numerous marble icons and, moreover, lead ones from the central and lower regions along the Danube. Iconographic content is presented in zones and the sacral structure is illustrated in the central zone: two horsemen heraldically depicted around the standing female figure represented in the center. Under one horseman is a lying human figure, and under the second one is depicted a fish; a three-legged table with a fish is illustrated under the female figure, and above her is Sol in a chariot. There are versions existing within this basic theme, but the central motif is constant. They are dated roughly to the 3rd -4th century AD and indirectly they are related to the cult of Mithra and Sol.

A large number of lead icons was found in our part of Posavina and Danubian regions, which leads to hypothesis that a workshop that produced them operated in Sirmum. Their meaning and fundamental nature of the cult are uncertain. A theory was proposed stating that a central female deity could be identified with Luna, horsemen with two spheres, as expressions of opposites, or two principles (geographic, military?), while Sol in a chariot is doubtless and represented in a habitual iconographic pattern.

Representations of Luna and Sol formed along a vertical line are, in certain variations, comparable with busts illustrating Sol and Luna shaped around the abscissa line of the image. The fact that these votive plaques appeared only in a particular region by the Danube denies the possibility of an imperial cult that should have been widely manifested across the Empire. But, it is probable that here an amalgamation of the imperial and a local cult occurred in Aurelian’s persona, and probably in Probus’ as well. A number of plaques and their iconographic and certainly sacral consistency indicate a certain official character of this cult. Are they a particular expression of the cult of emperors who were of Pannonian origin?

A vertical sacral structure of the representation can be interpreted as Luna, who is equaled to an empress (Severina), bearing in mind that during this period empresses were illustrated with Luna’s moon cycle, and Sol was equaled to Aurelian. Presence of the Empress, that is to say Luna, on the objects that had strongly military character wasn’t unusual; quite the opposite, the most frequent inscription on reverse of Severina’s coins was CONCORDIAE MILITUM.

Within the framework of this iconographic context the imperial scenography is interesting, which was mentioned in historical sources on the occasion of the arrival of emissaries of the defeated Allemani. Aurelian received them in the camp’s headquarters demonstrating a military grandiosity through which the greatness of Rome was expressed. The legion was lined in perfect order and silence, chief commanders with emblems of their rank were riding on horses placed next to the throne where the Emperor was sitting; behind the throne were figures of the members of the regal court and illustrations of former emperors. When Aurelian assumed his place, the Barbarian emissaries fell down under his feet and under his generals were sitting atop horses.

***

The head

The partially damaged head from an unknown archaeological site in Serbia was modeled in the tradition of realist portraiture that was characteristic for the epoch of military emperors. Smooth surfaces on faces, graphical treatment of eyes and nasal wrinkles indicate the period of the last third of the 3rd century AD. The wide oval face, rounded head and energetically protuberant beard in this portrait looks like Aurelian’s representations on coins where his rustic Pannonian origin and military career of this emperor can be recognized.

*** Hyperborea

Deer are pulling a vehicle of a chariot in which Apollo reaches the hyperborean distances. Representation of Aurealian in chariots pulled by deer symbolizes his triumph in the north over the Sarmatians or Goths. But the motif of deer hunting, which appears on funeral monuments, a toreutics and glass dishes also signifies the apotheosis, the reached hyperborean land of spiritual harmony and return. Achilles, whose tomb his mother Thetis built at the confluence of Danube, the hyperborean frontier, is also a symbol of the northern triumph’s pathway and of a personal apotheosis. Aurelian follows Achilles’ course (cursus Achilleus) during his triumph over the Goths on the Lower Danube when he was glorified with the title of Gothicus Maximus.

*** The winner

In a tomb from Zemun (Taurunum) dated to Late Antiquity were discovered two sash sheaths made of bronze plate with the representation of a horseman in the attacking position of a triumph over the fallen enemy. This theme, well known in Roman imperial iconography, is derived from an example whose author was Lisipus, that being the equestrian statue of Alexander the Great above a defeated enemy. The inscription Sol inv (inctus) on one of the sheaths would point to Aurelian, who identified himself with the Invincible Sun.

|